Early Life of James McBey , livre ebook

84

pages

English

Ebooks

2010

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

84

pages

English

Ebooks

2010

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Publié par

Date de parution

01 juillet 2010

Nombre de lectures

3

EAN13

9781847675873

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

1 Mo

Publié par

Date de parution

01 juillet 2010

Nombre de lectures

3

EAN13

9781847675873

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

1 Mo

Contents

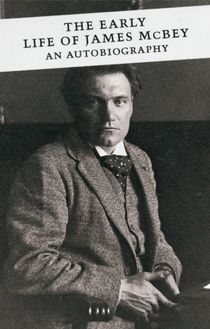

List of Illustrations

Introduction

THE EARLY LIFE OF JAMES MCBEY

Epilogue

List of Illustrations

1 . James McBey’s grandmother, Mary Gillespie. Painting (1901)

2 . James McBey’s mother, Anne Gillespie.

3 . James McBey, aged three.

4 . Boys Fishing. Etching (1902)

5 . The Blacksmith’s Shop. Etching (1902)

6 . Portsoy Harbour. Etching (1903)

7 . Enkhuisen Harbour. Etching (1910)

8 . The Mill, Zaandijk. Etching (1910)

9 . Hoorn Cheesemarket. Etching (1910)

10 . A Volendam Girl. Etching (1910)

11 . Omval. Etching (1910)

12 . The Cowgate, Edinburgh. Etching (1904–5)

13 . Inverleith. Etching (1904–5)

14 . Warriston Close. Etching (1908)

15 . Herring Fleet, Aberdeen. Etching (1909)

16 . Waiting for the Boats, Portlethen. Etching (1909)

17 . The Dean Bridge, Edinburgh. Etching (1904)

Introduction

James McBey’s life was filled with dramatic events and coincidences. They came unsought but not unacknowledged: he recognised them as turning points, links in a chain which, as he looked back, stretched behind him to the Buchan of his birth and youth. His life thereafter was filled with adventures and incidents, the telling of which kept his friends spellbound as he recounted them in his gentle but resonant voice and with the Scottish accent of his birthplace.

Although his life began in bleak, harsh circumstances, the chain of events that took him through so many strange places and unusual meetings did not always lead upward. The story of his early life ends on the brink of his first, spectacular success. The immediate warm reception of his first London exhibition in November 1911 and the quick sale of his prints that followed led to a triumph unbroken, even enhanced, by the First World War, and his new experiences as a war artist. Soon after the war the demand for his etchings was so great that the entire edition would be sold out immediately, to be resold at once at prices that no other living artist commanded. But the market for contemporary etchings ended with the Great Depression and, curiously, saw no revival for fifty years. McBey, unperturbed by the loss of the principal source of his reputation and income, worked for the rest of his life mainly in oils and watercolours. Since his death in 1959, his work has been rediscovered, and there have been an increasing number of exhibitions of it; besides this book, originally published in 1977, his long attachment to Morocco has been celebrated in James McBey’s Morocco by Jennifer Melville, with Michael Davidson’s photographs, published in 1991.

The story of how he came to write down his memoirs of his early life and how, much later, they came to be published is itself dramatic and surprising. After his sudden success in London, interviews and pieces relating to his life as well as his work constantly appeared in the press, and since the early thirties he had been pursued relentlessly by a publisher to write his autobiography. But it was not until after the Second World War, spent in exile from his beloved Morocco in America, that he found the time to embark on it. He had returned to Morocco, but, overwhelmed by the visual richness and the starvation that preceded it, could not find his artistic touch. He turned to writing his life story instead. He began it in the winter of 1947 during a patch of bad weather that made painting impossible. When he had finished the account of his life up to the point where he abandoned his safe but constricted career in the Aberdeen bank and risked his chance as a professional artist, he paused. His wife Marguerite carefully typed out the manuscript for him, and he sent it to his friend and patron, Η. Η. Kynett, in Philadelphia.

Encouragement was badly needed, but Kynett found the text too bleak and stark. He did not appreciate the spare vigour of the writing, nor the drama of the tale of an artistic talent forcing itself irresistibly through opposed and unyielding surroundings, like water through granite. Without the stimulus of Kynett’s sympathy and professional advice, McBey wrote no more. After his death, Mrs McBey, who had from the outset realised the value of what he had written, tried to get it published: Rupert Croft-Cooke was asked to complete it, by writing a continuation; the Aberdeen University Press provided estimates for a privately printed edition of McBey’s text alone. But neither availed; the manuscript came to rest in the drawer of a table in the room off his studio in London where he kept the collection of white paper, begun with a view to using it for his etchings, but continued for the pleasure he got from the visual and tactile qualities of paper as such.

In the event it was the paper that broke the deadlock. Mrs McBey offered the paper as a gift to Harvard University, and Roger Stoddard of the Houghton Library there asked me to examine and report on it. I did so, and the outcome was the publication of The McBey Collection of Watermarked Paper , a set of portfolios of specimens of the different stocks he had collected, with a catalogue raisonné by Colin Cohen. But in the process I happened on the manuscript of the McBey memoir, began to read it idly, and then with ever increasing intensity. It was a winter afternoon that wore on into the evening, but I read until McBey’s rough but calligraphic script was all but invisible, not daring to stop and switch on the light lest it break the spell.

As soon as I could I asked Mrs McBey about the manuscript. She told me how it came to be written, and what happened afterwards. It seemed to me unthinkable that such a masterpiece should remain unpublished, and I enquired diffidently if I might try where others had failed. Mrs McBey lent me the typescript, and I laid it before my colleagues at the Oxford University Press. They were as taken with it as I had been. Together, we worked out a scheme with Mrs McBey, that the original text should be printed exactly as it stood, with only a brief epilogue, an outline of his subsequent career, a fragment of what might have been a full autobiography.

This fragment, however, is complete as it stands. As an account of the rigour of life in Aberdeen and Buchan at the turn of the nineteenth century, it is both full and vivid. It also explains exactly how a native talent of exceptional strength was discovered and self-taught, and finally broke out of the shackles of ignorance and an inhospitable background. It is a wholly absorbing story, a small masterpiece, told with economy of words, simple but chosen with immense care.

Originality and economy were gifts that McBey applied not only to drawing, painting, and engraving, but to everything he had to do in life. It is not surprising, then, that he should have mastered the art of writing when he gave his mind to it. The sheets are firmly written in pencil, with few crossings-out or afterthoughts. All the vividness of his speech is preserved, as was the case in his letters, and this gives his writings a freshness which more practised writers will envy. There is every evidence that he would have continued to write the rest of this story with equal zest and assurance. Although the end comes just as he is poised to move to London and begin his professional career, the first part of the story ends in fact as he walks out of the bank for the last time. The journey to Holland immediately after, which he intended only as a break, was so entirely different, opened such wide horizons, both visual and spiritual, that it was the beginning of a new life.

The farewell to Scotland from the battlements of Stirling Castle was like so many other dramatic moments of his life highly significant and frequently attached to places. They were all religiously entered into his pocket diary in a minute and neat hand. These diaries and his own excellent memory were the material on which he drew in writing the account of his early life.

McBey continued to keep his diaries until his death, and they provided the record of events on which the epilogue was based. Mrs McBey’s vivid memory of events recounted by him and, later, shared with her, made it possible to describe the period in more than bare detail, thanks to the careful record made by her and the late Lady Caroline Duff. Even so it is designed only as an attempt to answer some of the questions that McBey’s own story raises. A full account of his life and work must wait for another occasion.

The illustrations are an important addition to the narrative. McBey always felt a strong sense of destiny with a compulsion to preserve even the smallest mementoes of his life, including a surprising number of photographs of his family and early life, from the smithy to the bank. These are amplified by some of his own paintings and prints, chosen to represent his work at the time and to provide a visual background to the story. These documents have been largely deposited at the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum by Mrs McBey. I am grateful to the Director, Mr Ian McKenzie Smith, and his staff for their continued kindness in making them available. But my principle debt is to Mrs Marguerite McBey, without whose encouragement and determination this work would never have received a first, still less a second, edition. By taking great pains to ensure the accuracy of the text and equal care to prepare and list the illustrations in the first edition, she made a far larger contribution to this book than would appear at first sight. I must also record my gratitude to my former colleagues at Oxford University Press, Catherine Carver and Susan le Roux, for their work on the text.

When The Early Life of James McBey first appeared, it was not widely reviewed. But two notices, those in The Times Literary Supplement and The Listener , both percipiently noticed its classic quality, that it could be fairly compared with any of the great autobiographies of the past. I am delighted that this quality has been recognised by Canongate Press, whose e