The Arthur of Medieval Latin Literature , livre ebook

142

pages

English

Ebooks

2011

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

142

pages

English

Ebooks

2011

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Publié par

Date de parution

15 mars 2011

Nombre de lectures

1

EAN13

9781783164530

Langue

English

Publié par

Date de parution

15 mars 2011

Nombre de lectures

1

EAN13

9781783164530

Langue

English

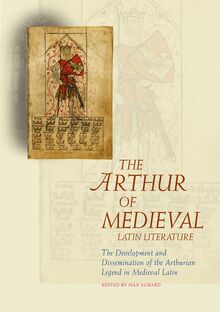

THE ARTHUR OF MEDIEVAL LATIN LITERATURE

ARTHURIAN LITERATURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

VI

THE ARTHUR OF MEDIEVAL LATIN LITERATURE

THE DEVELOPMENT AND DISSEMINATION OF THE ARTHURIAN LEGEND IN MEDIEVAL LATIN

edited by

Si n Echard

CARDIFF UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS 2011

The Vinaver Trust, 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright owner s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to The University of Wales Press, 10 Columbus Walk, Brigantine Place, Cardiff, CF10 4UP.

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7083-2201-7 e-ISBN 978-1-78316-453-0

The right of the Contributors to be identified separately as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77, 78 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH

THE VINAVER TRUST

The Vinaver Trust was established by the British Branch of the International Arthurian Society to commemorate a greatly respected colleague and a distinguished scholar

Eug ne Vinaver

the editor of Malory s Morte Darthur . The Trust aims to advance study of Arthurian literature in all languages by planning and encouraging research projects in the field, and by aiding publication of the resultant studies.

ARTHURIAN LITERATURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

Series Editor

Ad Putter I The Arthur of the Welsh , Edited by Rachel Bromwich, A. O. H. Jarman and Brynley F. Roberts (Cardiff, 1991) II The Arthur of the English , Edited by W. R. J. Barron (Cardiff, 1999) III The Arthur of the Germans , Edited by W. H. Jackson and S. A. Ranawake (Cardiff, 2000) IV The Arthur of the French , Edited by Glyn S. Burgess and Karen Pratt (Cardiff, 2006) V The Arthur of the North , Edited by Marianne E. Kalinke (Cardiff, 2011) VI The Arthur of Medieval Latin Literature , Edited by Si n Echard (Cardiff, 2011)

CONTENTS

Preface

Ad Putter

Abbreviations

Introduction: The Arthur of Medieval Latin Literature Si n Echard

Section One The Seeds of History and Legend

1 The Chroniclers of Early Britain

Nick Higham

2 Arthur in Early Saints Lives

Andrew Breeze

Section Two Geoffrey of Monmouth

3 Geoffrey of Monmouth

Si n Echard

4 Geoffrey and the Prophetic Tradition

Julia Crick

Section Three Chronicles and Romances

5 Latin Historiography after Geoffrey of Monmouth

Ad Putter

6 Glastonbury

Edward Donald Kennedy

7 Arthurian Latin Romance

Elizabeth Archibald

Section Four After the Middle Ages

8 Arthur and the Antiquaries

James P. Carley

Bibliography

PREFACE

This book forms part of the ongoing series Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages. The purpose of the series is to provide a comprehensive and reliable survey of Arthurian writings in all their cultural and generic variety. For some time, the single-volume Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages: A Collaborative History (ed. R.S. Loomis, Oxford, 1959) served the needs of students and scholars of Arthurian literature admirably, but it has now been overtaken by advances in scholarship and by changes in critical perspectives and methodologies. The Vinaver Trust recognized the need for a fresh and up-to-date survey, and decided that several volumes were required to do justice to the distinctive contributions made to Arthurian literature by the various cultures of medieval Europe. The Arthur of the Medieval Latin Literature is primarily devoted to medieval Arthurian texts composed in Latin, from all across Europe, but it also takes account of the interplay between Latin and vernacular traditions and of the influence of medieval Latin Arthurian writings on the literature of later periods, particularly that of the Early Modern period.

The series is mainly aimed at undergraduate and postgraduate students and at scholars working in the fields covered by each of the volumes. The series has, however, also been designed to be accessible to general readers and to students and scholars from different fields who want to learn what forms Arthurian narratives took in languages and literatures that they may not know, and how those narratives influenced the cultures that they do know. Within these parameters the editors have had control over the shape and content of their individual volumes.

Ad Putter, University of Bristol (General Editor)

ABBREVIATIONS AC Annales Cambrie ALMA Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages DEB De excidio et conquestu Britannie ELH English Literary History EETS Early English Text Society FH Flores historiarum HB Historia Brittonum HE Historia ecclesiastica gentis anglorum HRB Historia regum Britannie ODNB Oxford Dictionary of National Biography RS Rolls Series VM Vita Merlini

INTRODUCTION: THE ARTHUR OF MEDIEVAL LATIN LITERATURE

Si n Echard

. . . codicem illum in Latinum sermonem transferre curaui 1 [I have taken the trouble to translate the book into Latin]

In the preface to his Historia regum Britannie ( c. 1138), Geoffrey of Monmouth claims to be translating into Latin an ancient book in the British tongue, given to him by Walter, archdeacon of Oxford. The status of this book has been a subject of controversy ever since, and more than one of the essays in this collection will touch on Geoffrey s sources and possible motives. I open this introduction with the single line above, however, because it contains two crucial words - codicem and Latinum . Codex is an unequivocal word, an assertion of textual materiality, and Latin is the language of textuality in Geoffrey s day. 2 It is also the language of authority: Latin is, as Bakhtin puts it, The word of the fathers . 3 To be litteratus meant to be able to read and write Latin, and for much of the Middle Ages, such skills belonged largely to a clerical elite. 4 Even the rise of the vernaculars as vehicles for literary high art could not shake the status of Latin as the medium for certain kinds of knowledge, nor indeed the sense that codices are the proper repositories for that kind of knowledge. Latin, in short, was serious business. This is not to say Latin could not be satirical, irreverent, subversive, funny - it could be all of these things. 5 There was also a great deal of bad Latin in the Middle Ages, pedestrian, overreaching, or just plain wrong. But for the educated litterati , Latin came as part of a package with a certain kind of education, one that included self-conscious awareness of matters of style at the level of word, argument and form. 6

Geoffrey asserts that he has accepted Walter s commission with humility: I have not collected flowery words from foreign gardens, but have instead been content with my own rustic style and my own reed pipe. 7 His readers are expected to recognize the modesty topos and its classical antecedents, and they are expected as well to see the degree to which his preface invokes what we might think of as the community standards for medieval Latin histories. Geoffrey names his source, compliments his patron, and asserts straightforward practice while also displaying technical skill. 8 Similarly when Geoffrey closes his history by warning other historians to keep silent about the kings of the Britons, because they do not have the book in the British language which Walter, archdeacon of Oxford, brought from Wales , 9 he is targeting very precisely the habits of mind of his contemporaries by asserting that he possesses a written source which they do not. They may suspect that he is lying - indeed some of them charged that he was - but part of the overwhelming success of Geoffrey s Historia can be attributed to his historiographical skill, even if in the service of what William of Newburgh (1135/6- c .1198) would call ridicula figmenta . 10 Geoffrey would not be the only Latin historian to fabricate a useful documentary source, nor is he the only Latin historian to embellish fact , embracing the latitude granted by history s acknowledged place as one of the rhetorical arts. 11 Geoffrey s opening and closing remarks amount to a greeting to his peers: if they are also an implicit challenge, or the sly acknowledgement of a long joke at their expense, it is important to recognize that the terms are the shared inheritance of Latinity.

This volume, then, is rather different from those that have preceded it. While other Arthurian traditions can be treated through a lens that to some extent at least aligns language with ethnic or geographical identities, the Latin tradition is the product of a shared language and a particular kind of culture, but the language is not a birth tongue. Instead, like the attendant culture, it was acquired through education. There is no one geographical place to which this tradition can be assigned. There is perhaps a sense that Arthur appropriately belongs to the British - when a transplanted Italian, Polydore Vergil ( c .1470-1555), raised questions about two foundational British heroes (Brutus and Arthur), the response from English historians suggested nationalistic pride and a touch of xenophobic hostility. 12 But British is a vexed term - many of the works to be dealt with in these pages were produced at the time of the Angevin kings, for example, a period in which a Latinate courtier-cleric might find himself in the service of an empire that included parts of what we now call England and France. Geoffrey opens his Historia with the account of the founding of Britain by the Trojan refugee Brutus, but Geoffrey s own sympathies and ethnicity - was he Norman? Breton? Welsh? - have long been a matter of debate. There is pre-Galfri